British Land distribution policy and its consequences..

By: Tarique Khan Javed

President, Overseas Pakistani Investors Forum.

Dated 6 Nov 2008

Greatest expansion of Agriculture in India:

Between 1885 and the end of British rule in 1947, the canal-irrigated area in the Punjab, excluding the princely states, increased from under 3,000,000 to around 14,000,000 acres. The great bulk of this increase took place in the canal colonies, which experienced thereby the greatest expansion in agricultural production in any part of South Asia under the British. The vast landed resources thus created in the canal colonies had a profound impact on economy and society in the Punjab. From the significant economic growth that ensued, the Punjab obtained its most promising prospects of economic development in recent history. The extent to which agricultural growth allowed the preconditions for successful development to emerge was greatly influenced by the nature of land utilization in the canal colonies. “Colonization” or the motives and methods involved in the settlement of these new lands, determined the character of the emergent society and the degree to which that society was capable of structural transformation from its existing state of economic backwardness.

The colonization process was molded by two forces: the state and the social structure. The former was important because it controlled land distribution: the canal colonies were situated in tracts designated as crown waste lands. This transferred ownership of these areas to the state, and allowed it to dispose off the land according to its discretion. Since the state also controlled the canal system and the water source, agriculture itself became dependent on the will of the Ruling Authority. The ownership of both land and water gave the Central power virtual control over the means of production, thus greatly enhancing its authority over society. The role of the state was made manifest in the colonization policy that provided the framework for land distribution in the canal colonies. State policy determined matters both great and small, ranging from the formulation of the general principles governing land distribution to the implementation of measures in the minute circumstances of the local arena. Here was interventionist imperialism, extensively engaged in demographic and economic change.

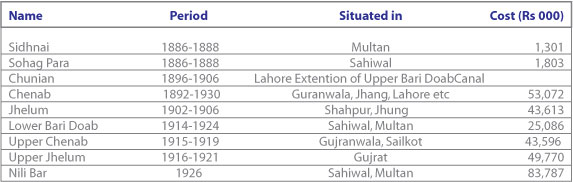

Canal projects:

Virgin Land and a classed society:

It was this element of colonization, born out of the inadequate demographic resources of thee doabs that distinguished canal construction in the western Punjab from that further east. In other parts of northern India, such as the United Provinces, the canals constructed during British rule brought irrigation to already settled tracts. They supplemented existing agricultural systems based on barani (rain fed) cultivation, and did not therefore require any in-migration. In the western Punjab, owing to the insufficiency of rainfall, agriculture was far more dependent on irrigation, and traditional irrigation systems relied on wells and seasonal inundation, traditionally allowing cultivation only in tracts contiguous to rivers. The extensive interfluves, left elevated through river action, remained unirrigated. The irrigation network that emerged after 1885 was based on perennial canals that led off from river-spanning weirs and headworks. This rendered cultivable the upland plains that had hitherto remained inaccessible to the smaller-scale and technologically less sophisticated traditional irrigation methods. The combination of migratory colonization with the great dependence of cultivation on canal water supplied by a centralized authority created in this region a truly “Hydraulic” society, such as could only exist in a diluted from further east because of the preponderate influence of barani agriculture.

Formation of unjust but obedient “Hydraulic” societies:

The end product of state policy was the structure of landholding that emerged in the canal colonies. Colonization had a major impact on people and society in the Punjab. Since the manpower for agrarian growth came almost entirely from within the province. Existing stratifications and hierarchies in the Punjabi population were bound to be projected onto the new sphere. In rural society there existed extremes of wealth between large landowners on the one hand and poor cultivators and landless laborers on the other. Between these were intermediate layers of richer peasants and medium-sized landlords and, in addition, the urban-based strata of the bourgeoisie and working class. Only the last, constricted in size and preindustrial in nature, was unimportant to colonization until colony towns came into being.

Class divisions were not the only focus of socioeconomic distances: the caste system pervaded human consciousness and divided society into groups of superior and inferior status. The “superior” castes were also economically and politically dominate, for they followed elite occupations, and the means of production were concentrated in their hands. Because of their entrenched power, such groups were advantageously placed to exploit new agricultural and commercial opportunities. The extent to which existing inequalities in society led to an unequal sharing of resources is central to a discussion of the importance of the canal colonies to the Punjab.

New Canal colonies in Sindh:

In Sindh were British Rule started in1843 the first major project - Lyodd Barrage was constructed at a cost Rs 22 crores in 1932. It gave 7.5 million acres of new perennial irrigated land that transformed the deserts of Sindh into a bread basket. Here also land was distributed on commercial terms or keeping Empires need in mind. That is why the project cost was recouped with the projected 10 year period.

Distribution of land ownership in Pakistan and provinces, 1950-55:

During this period 1.2 percent of owners owning 100 acres and above land owned 31.2 percent of all land in Pakistan. While those owning between 25-100 acres constituted 5.7% of land owners and they owned 21.8% of all land. Those owning between 5-25 acres constituted 28.7% of land owners and owned 31.7% of all land. Small farmers owning 5 or less on the other hand comprised 64.4% of land owners but owned only 15.3% of all land.

The two major provinces Punjab and Sindh accounted for 38.5 million acres (or 79%) of land out of total 48.6 million acres for the country. In Punjab 0.7% owners having land above 100 acres owned 23.5% of all land in the province. While in Sindh 8% owned 54.4% of all land. Those owning between 25-100 constituted 4.1% and 16.2% but owned 21.9- 23.2%, respectively.

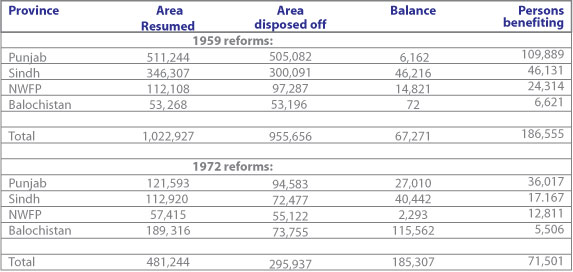

Progress of implementation of land reforms up to June 1994(hectares):

Unimplemented Land Reform Act of 1977:

Land Reform Act of 1977 calling for reduction in maximum land holding of irrigated land from 150 (as per 1972 Act) to 100 and unirrigated 300 to 200; still awaits implementation.

Other than 2.7 million Government land distribution which comes in to discussion from time to time there is no talk of land reform in Pakistan. Even distribution of Government land is delayed on one pretext or the other while the millions of poor landless people keep pleading.

Land reform need of the hour:

In 2002 Prime Minister Jamali of Muslim League (Q) declared that the issue of land reforms was over in Pakistan and that the current holdings were optimum for productivity.

If PPP wants to prove that it is different from MLQ and really represent the poor they should implement the shelved 1977 Land Reform Act passed by National Assembly, in the dying days of Shaheed Zulfiqar Bhutto’s rule. Zai Ul Haq obtained a Fatwa from Ulmas and declared the act of resumption and redistribution of land as Un-Islamic.

Thirty one years have passed since its passage and no one even talks about its non implementation. Use of Islam to block provision of justice and relief for the poor is most distressing. This is the best way to alienate people from Islam and lead them to adopt non religious ideologies like that of Communism in China.

The fastest means to reduce poverty is implementation of this Act and therefore PPP and its allies MQM and ANP should make this a top priority.